I was honoured to inaugurate this year s Avid Readers Forum conversations as the Lead Reader, on a theme dear to my African Feminisms scholarship. Before diving into my reflections on the conversation, it is instructive to appreciate that African Feminisms is an active epistemic struggle and its battleground is in the everyday. Recent incidents of intentional killing of women, femicide, draw me to Toni Morrison s concept of re-memory, a personal or collective familiar or unfamiliar traumatic memory,[ii] to imprint in our minds that these manifestations of gendered violence run through space and time. There is also Amina Mama s acknowledgement of the hidden struggle against gender-based violence, the one that is neither written nor spoken about:

It must be said that for every abused woman who makes the headlines by being killed or maimed, or for each of those who suffer in clubbed-down silence, there must be many thousands who receive local support and who engage in a hidden struggle for their survival and dignity a continuous struggle that neither receives nor demands acknowledgement.[iii]

This blog piece is an attempt to reprise the intellectualism at Sawia in five key points as we unpacked Ali Mazrui s journal article. My aim is also to add my perspectives to the piece for first-time readers of decolonial thinkers like Mazrui. Even so, my method is anchored in Paulo Freire s problem-posing education, which dictates that no teacher is a monolith of knowledge, instead, education (the type against all forms of oppression) is dialogue where teacher imbibes from student and student from teacher to collectively pursue their full humanity (emancipation).[iv]

First point: Understand Mazrui s theoretical framework, which he rapidly invites us to perceive with him in the first paragraph of the article:

There are three levels of sexism in the world-benevolent, benign, and malignant. There are also three levels of redemption from sexism for the Black woman liberating the Black woman, centring the Black woman, and empowering the Black woman. While illustrations will be drawn mainly from the Black world, and especially from Africa, comparison with the rest of the world will inform much of the following analysis.[v]

Mazrui s Triple Heritage theory is introduced to the reader when he distinguishes the black world in Africa from the rest of the world. According to the Triple Heritage theory, the African identity is fractured in three respects namely, African indigenous, Euro-Christian (owing to late 19th Century colonisation) and the Islamic civilisation. Osogo Ambani adds a fourth fracture on globalisation[vi] from emerging imperialistic fusses about Big Tech, Big Data, Big Pharma, Big Oil, Big Food, Big Agriculture as well as the long-standing revolutionary influence of Pan-Africanism and the budding Afro-futurism. Together, African means a clash of many civilisations.

Second point: Understand the context of the time of publication. In 1993, the date of publication of this article, there was a growing body of knowledge crystallised as decolonial thought/thinking, which overflowed/ swelled up during the decolonial turn, the twentieth century, when many disciplines and discourses, including Pan-Africanism and feminism, vehemently opposed coloniality.[vii] One lead thinker of decolonial feminism, Argentinian scholar Maria Lugones, described the oppression-resistance construction of the colonial woman very aptly especially on the point of continuous resistance:

Instead of thinking of the global, capitalists, colonial system as in every way successful in the destruction of its peoples, knowledges, relations, and economies, I want to think of the process as continually resisted, and being resisted today. And thus, I want to think of the colonised neither as simply imagined and constructed by the coloniser and coloniality in accordance with colonial imagination and the strictures of the capitalist venture, but as a being who begins to inhabit a fractured locus constructed doubly, who perceives doubly, related doubly, where the sides of the locus are in tension, and the conflict itself actively informs the subjectivity of the colonised self in multiple relation.[viii]

Lugones two-faced conflict finds credence among many other writers explanations on the African s identity crisis as these writers were active during the decolonial turn. You may want to read about citizen and subject conflict as constructed by Mahmood Mamdani and the double-consciousness or two-ness by WEB Du Bois. Interestingly, Mazrui s feminism, writes Horace G Campbell, was enriched by his childhood growing up in a patriarchal atmosphere of colonial Kenya, and when he travelled to United States of America in 1971 where he was confronted not only with racial oppression but, pointedly, the progressive feminist movement.[ix] This indeed fomented his (un)learning and scholarship on the lived struggles of African men and women.

Third point: Perhaps it was to achieve harmony with the Triple Heritage theory s trinity, but the three forms of sexism and the three redemptive solutions of sexism occur simultaneously; they are interrelated. As Lugones invites us to think doubly, Mazrui engages us triply. Briefly, benevolent sexism is generous/protective towards the underprivileged gender, benign sexism is harmless and recognises gender differences, and malignant sexism subjects women to economic manipulation, sexual exploitation and political marginalisation.[x] Liberating means freeing the woman, centring is illumining her, empowers as the term reads confers power.

Molara Ongundipe-Leslie, a lead African Feminist, in her critique of the journal article (published just after Mazrui s piece in the same volume) warns that the categories of sexism are too tidy to yield any serious discourse on sexism. She asserts: All sexism is negative and undesirable because so-called benign and benevolent sexism are often expressions of the malignant. Does not benevolent sexism often merely reinforce the malignantly sexist organisation of society? [xi] Elsewhere, she calls out Mazrui s arguments as simplistic, patronising, retrogressive and absurd. In fact, Mazrui is an outsider, he should not speak for women. I will address the question, it is a right question as philosophers say, in the next section. I also take heed as Ongundipe-Leslie instructs as these issues play out in constructing African Feminisms and we cannot dismiss them. For emphasis, we are in an epistemic not emotive struggle. Besides, Ongundipe-Leslie did not remonstrate without a solution, she gave us Stiwanism, a strand of African Feminisms. In her words:

I have advocated the word Stiwanism instead of feminism, to bypass the combative discourses that ensue whenever one raises the issue of feminism in Africa. The word feminism itself seems to be a kind of red tag to the bull of African men. Some say the word by its very nature is hegemonic, or implicitly so. Others find the focus on women in themselves somehow threatening. Some who are genuinely concerned with ameliorating women s lives sometimes feel embarrassed to be described as feminist. Stiwa is my acronym for Social Transformation Including Women in Africa. [xii]

Fourth point: Having understood these bigger picture epistemic worlds one can comprehend and apprehend Mazrui s rhetorical posture on the three categories of sexism, which depend on the contexts/main civilisation (of the three) at play. Consider how he juxtaposes Western culture of male chivalry of sparing women heavy loads (including opening doors and compliments) as benevolent sexism translated into an African perspective:

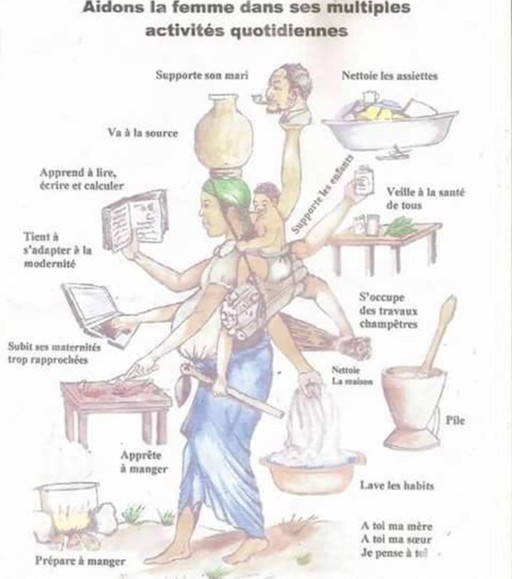

How much benevolent sexism is there in Africa? And what forms does it take? Are African women spared carrying heavy loads by their men? ...Indeed the African woman in the village has had to learn incredible balancing skills firewood on her head, a baby on her back, and a basket of cassava in one hand and a basket of yam in the other.[xiii]

Note that this is a portrayal of African women that may offend. Everjoice Win describes it best when she writes that the preferred woman, especially when translated to the Western world, is often poor, powerless, invariably pregnant, bare-footed and laden with children or goods fastened on her back or head .[xiv] In 2021, I received this supernatural woman image below with the caption Happy International Women s Day; see her many tentacles attending to all of societies daily burdens. As a graduate student at the time, I was deeply offended, but later I have come to appreciate that the image represents real economic (class) and political power questions that African women encounter today. The new African woman, continues, moves and carries out obligations between the urban (modern) and local (traditional) with ease, occupies powerful positions at both local and international level, and is neither too poor nor too rich.[xv]

There was a sense at Sawia (packed with new women), that Mazrui s examples of sexism were outdated and did not capture their present-day realities. Let us reflect on three instances in Mazrui s rhetoric fashion: Is bridewealth (from the groom to the bride s family) a form of benevolent sexism?[xvi] Is the subculture of cosmetics, jewellery and perfume; of women spending more time, energy and resources on making themselves attractive a benign form of sexism?[xvii] Was the martyrdom of Kimpa Vita of Angola-DRC or Alice Lenshina of Zambia because of their movements to indigenise European religions at the height of European colonisation malignant sexism?[xviii] Additionally, I asked the audience, why are there more women at Kenyan law schools than men, and why do they perform better than men academically, some even take up university leadership positions while men show disinterest? Could it be a depiction of how men are treated outside the law school? For example, there are more male victims of unlawful police killings and unemployment, which is cruel and dehumanising. Therefore, this answers Ongundipe-Leslie s question as thinking triply allows us to pursue a fuller and less partial account of the African woman s experience with sexism in whatever form or guise.

Fifth point: Gender inequalities reveal contradictions, what Mazrui calls the paradox of gender, which bring to the fore the three solutions; liberating, centring and empowering. The three solutions are interrelated, as [a] woman can be at the centre without being empowered; a woman can be liberated without being either centred or empowered .[xix]

But what is the paradox of gender? It consists of three propositions: 1) Among humans, the senior partner in the creation of new life is the female of the species (woman as mother); 2) Among humans, the senior partner in the destruction of life is the male of the species (man as warrior); and 3) The power of destruction has given the male of the species political dominion over the female (man as ruler).[xx]

Ecofeminism, another strand of African Feminisms, is constructed along the three propositions in the context of ecology (hence the eco in ecofeminism). Vandana Shiva and Maria Mies expose the male-driven Green Revolution for its fa ade in improving food security through technology by destroying the earth and the age-old role of women as custodians of the earth. In their words, We see the devastation of the earth and her beings by the corporate warriors, and the threat of nuclear annihilation by the military warriors, as feminist concerns .[xxi] While Mazrui in the journal article writes that the rural woman is centred as she is custodian of fire (in charge of firewood), custodian of water (ensuring its supply in the home) and custodian of earth (cultivating land), [xxii] ecofeminists would say the Green Revolution alleges to centre the woman but neither liberates nor empowers her. Hence, I agree with Mazrui s ultimate recommendation that we need to dismantle sexism by moving towards genuine power-sharing between men and women.[xxiii]

I think one way is to affirm that women have gender-specific knowledges over nature, which are different from men s. Ariel Salleh, a lead ecofeminist, explains:

A first difference involves experiences mediated by female body organs in the hard but sensuous labours of birthing and suckling. A second difference follows from women s historically assigned caring and maintenance chores that serve to bridge men and nature. A third difference involves women s manual work in making goods as farmers, cooks, herbalists, potters, and so on. The fourth difference involves creating symbolic representations of feminine relations to nature - in poetry, in painting, in philosophy, and everyday talk. Through this constellation of lay labours, the great majority of women around the world are organically and discursively implicated in life-affirming activities, and they develop gender-specific knowledges grounded in this material base.[xxiv]

This is why I have emphasised that this is an active epistemic struggle. It is about knowing women and doing right by them. Back to Morrison, African Feminisms are as limitless as the experiences of all living women and those who lived in case you forget, you will surely encounter a re-memory of this struggle against sexism. At the close of the Avid Readers Forum, I promised to return, if allowed, to discuss more reads on African Feminisms, as part of my contributions to the struggle.

[i] Tutorial Fellow and LL.B Research Coordinator at Kabarak Law School.

[ii] Toni Morrison, Beloved, Vintage, 2019 reissue, 43-44. Eve Moeykens-Arballo, Re-visiting re-memory: Beloved vis vis one never remembers alone one never remembers alone, 24 April 2024, <https://www.oneneverremembersalone.com/blog/eve> on 8 March 2025.

[iii] Amina Mama Sheroes and villains: Conceptualising colonial and contemporary violence against women in Africa in M Jacqui Alexander and Chandra Mohanty (eds) Feminist genealogies, colonial legacies, democratic futures, Routledge, 1997, 53.

[iv] Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the oppressed, 30th Anniversary edition, Continuum, 2000, 80, 84-86.

[v] Ali Mazrui, The black woman and the problem of gender: An African perspective 24(1) Research in African Literatures (Spring 1993) 87.

[vi] John Osogo Ambani, The peoples law: Toward a new common law for Africans 25(3) Journal of the Commonwealth Magistrates and Judges Association (2021) 24.

[vii] Nelson Maldonado-Torres, Thinking through the decolonial turn: Post-continental interventions in theory, philosophy, and critique An introduction 1(2) Transmodernity: Journal of Peripheral Cultural Production of the Luso-Hispanic World (2011) 1-2.

[viii] Maria Lugones, Toward decolonial feminism 25(4) Hypatia (Fall 2010) 748.

[ix] Horace Campbell, Ali Mazrui: Transformative education and reparative justice in Kimani Njogu and Seifudein Adem (eds) Perspectives on culture and globalisation: The intellectual legacy of Ali A. Mazrui, Twaweza Communications, 2017, 83, 91-92.

[x] Mazrui, The black woman and the problem of gender 87-92.

[xi] Molara Ongundipe-Leslie, Beyond hearsay and academic journalism: The black woman and Ali Mazrui 24(1) Research in African Literatures (Spring 1993) 106.

[xii] Molara Ogundipe-Leslie, Recreating ourselves: African women and critical transformation, Africa World Press, 1994.

[xiii] Mazrui, The black woman and the problem of gender 88.

[xiv] Everjoice Win, Not very poor, powerless or pregnant: The African woman forgotten by development 35(4) IDS Bulletin (2004) 61.

[xv] Win, Not very poor, powerless or pregnant: The African woman forgotten by development 62.

[xvi] Mazrui, The black woman and the problem of gender 88.

[xvii] Mazrui, The black woman and the problem of gender 91.

[xviii] Mazrui, The black woman and the problem of gender 92.

[xix] Mazrui, The black woman and the problem of gender 97.

[xx] Mazrui, The black woman and the problem of gender 95.

[xxi] Maria Mies and Vandana Shiva, Ecofeminism, 2ed, Zed Books, 2014,14.

[xxii] Mazrui, The black woman and the problem of gender 97.

[xxiii] Mazrui, The black woman and the problem of gender 103.

[xxiv] Ariel Salleh, Ecofeminism as sociology 14(1) Capitalism Nature Socialism (2003) 67.