King David Arita

The recognition of animal rights and welfare, particularly as pertains their health, gained substantial traction during the late twentieth century.[i] This was spearheaded by a series of efforts led by scholars and complementary institutions, shedding light on the rights and welfare of animals as sentient beings.[ii] The establishment of the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) operating under the umbrella of the World Health Organisation (WHO), further solidified the global commitment to animal well-being.[iii] In 2009, WOAH took a significant step in addressing the issue of stray dog population control by drafting comprehensive guidelines.[iv] The guidelines aimed to address and reduce the indiscriminate culling of stray dogs, particularly by discouraging the use of strychnine. The justification for this approach was twofold: to ensure public order and protect human health.[v] These efforts saw the escalation of stray dog populations on a global scale.

In Kenya, the local stray dog population has experienced a drastic surge in the last decade. Machakos County, for instance, has become a hotspot for the mushrooming stray dog population, estimated to reach an approximate of 259,394 dogs.[vi] This unregulated growth has raised concerns regarding human -dog interactions and the subsequent elevated risk of zoonotic disease transmission . These are diseases caused by transmission of germs from animals to human.[vii] The most well-known zoonotic disease is rabies and it poses a continual threat to human well-being. This disease is primarily transmitted through dog bites.[viii] The pressing question thus arises: can a balance be struck between respecting animal rights and safeguarding human health? This paper seeks to grapple with this complex issue, investigating possible solutions and strategies to achieve a harmonious equilibrium. By addressing the stray dog epidemic head-on and examining the controversy surrounding the risks posed to human health, this article navigates the challenging terrain where animal rights clash with the fundamental right to health for individuals.

Research reveals that there are more than a hundred zoonotic diseases that can be transmitted from dogs to human beings which inter alia are rabies, larva migrans and tapeworm larvae.[ix] Essentially, stray dogs play a vital role in maintaining and transmitting these zoonoses especially if they are unattended. As the population of stray dogs constantly increases, so do the chances of an outbreak of these zoonoses and their contraction by human beings. Recently, a rabies outbreak was declared in Machakos County causing the county to be one of the pilot areas for Kenya National Rabies Elimination Program.[x] Prior to this, the government of Kenya had formulated a five-stage strategic plan for the elimination of human rabies in Kenya through mass vaccination of dogs starting from 2014 to 2030.[xi] However, this plan is concentrated on domestic stray dogs hence slightly ineffective as there also exists exclusive stray dogs. Exclusive stray dogs are those that are at large with no supervision nor restrictions.

In essence, a conundrum is raised on whether to prioritise animal welfare as opposed to the right to health both of which are envisaged in the Constitution.[xii] The government of Kenya finds itself torn between upholding the right to health for its citizens and addressing the rights and welfare of animals, particularly exclusive stray dogs. On one hand, ensuring the health and well-being of the population is a principal responsibility, as it directly impacts the quality of life of individuals. The government must take measures to prevent and control the spread of zoonoses, which may include managing stray dog populations to minimise the risk of bites, injuries, and the transmission of diseases such as rabies. On the other hand, animals, including stray dogs, deserve consideration and compassionate treatment. Balancing these concerns becomes especially complex when implementing policies that may threaten animal rights while aiming to protect public health. Striving for a solution that respects both the right to health and the welfare of animals is a challenging assignment, requiring careful deliberation, comprehensive strategies among involved institutions in order to achieve a perpetual solution.

The guidelines on stray dog population control define a stray dog as any dog not under direct control by a person or not prevented from roaming. They further provide for the various categories of stray dogs which are: free-roaming owned dog not under direct control or restriction at a particular time, free-roaming dog with no owner, feral dog meaning a domestic dog that has reverted to the wild state and is no longer directly dependent upon humans for successful reproduction.[xiii] This definition has been adopted by the Control of Stray Dogs Bill.[xiv] The Kenyan legal framework has articulated the definitions of animals,[xv] domestic animals,[xvi] wild animals[xvii] and even canine animals.[xviii] However, none has comprehensively codified a definition for exclusive stray dogs.[xix] All these are stipulated for in national legislations. On the other hand, county legislations have taken a step further in providing for exclusive stray dogs and stipulate for the rules of engagement on occasions they are identified as such.[xx] Sadly, none has provided for their definition as well.

This illuminates a significant problem when it comes to delving into the salient element of stray dog population control which is identification. This requires officials tasked with impounding stray dogs to have the discretion of choosing which dog fits the description and which one does not. As a result, domestic stray dogs could be mistaken from exclusive stray dogs. As remedy for this, the Control of Stray Dogs Bill stipulates the way forward if a free roaming dog is caught. It outlines responsibilities of dog owners to their dogs one of them being to ensure their dog does not roam out of control in a manner that would pose a risk or cause nuisance to members of the public.[xxi] It goes further and states the penalty of violating the said obligations hence compelling owners to take cognisance of their dogs' whereabouts as part of their welfare. Therefore, if passed the Bill could provide a humane alternative in handling exclusive stray dogs.

Therefore, addressing the issue of exclusive stray dog populations in a moral and compassionate manner requires a comprehensive approach. The proposed measures include but are not limited to, the confinement of stray dogs, control of dog reproduction, putting up impounded dogs for adoption, and taking environmental steps to mitigate the resources (garbage) available for their consumption, are some of the crucial steps toward managing their population effectively.[xxii] It is critical to emphasise that all these measures should be carried out in a humane manner, taking into account the well-being of the animals involved. The inclusion of these measures both within the Control of Stray Dogs Population Bill and the Animal Protection and Welfare Bill[xxiii] demonstrate the government's commitment to finding a balanced solution that considers the rights of animals while safeguarding public health. These Bills be enforced and implemented with adequate resources, ensuring collaboration among relevant stakeholders, including government authorities, animal welfare organisations, and local communities. By combining these measures with educational initiatives on responsible pet ownership and raising awareness about the importance of animal welfare, Kenya can foster a society that respects the rights of both humans and animals thus promoting harmonious coexistence for the benefit of all.

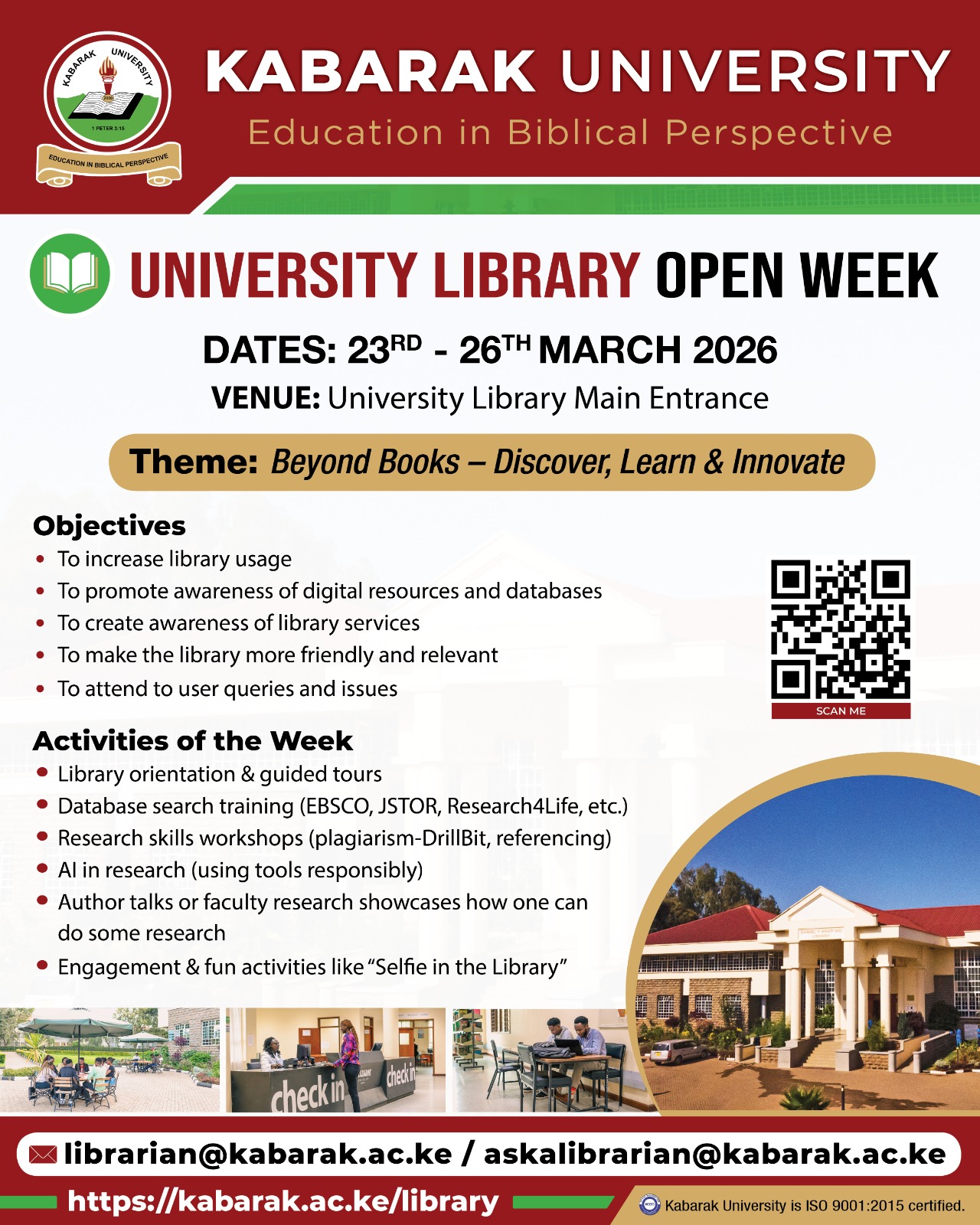

*The Author is an undergraduate student of law Kabarak University School of Law and the peer review editor of the Kabarak Law Review

[i] Karol Orzechowski, 'Animal rights movement: History and facts about animal rights' Fuanalytics, 9 April 2020.

[ii] Jeremy Bentham, Principle of Penal Law, vol II, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 1841; Peter Singer, Animal liberation: A new ethics for our treatment of animals, HarperCollins Publishers LLC, 1975.

[iii] Universal Declaration on Animal Welfare, Adopted by the International Committee of the OIE on 24 May 2007, 75 GS/FR PARIS, May 2007.

[iv] World Organisation for Animal Health, 'Guidelines on stray dog population control' ANNEX XVII (2009).

[v] World Organisation for Animal Health, 'Guidelines on stray dog population control' ANNEX XVII (2009), 16.

[vi] Tamara Kartal & Dr. Amit Chaudhari, 'Owned Dog Population and Knowledge, Attitude and Practices (KAP) Survey Report for Machakos County, Kenya' Humane Society International, 2017.

[vii] Sonya Angelica Diehn, 'Stray dogs problem' DW Global Media Forum, 8 January 2011 <https://www.dw.com/en/not-just-for-the-dogs-strays-problem-is-also-human-rights-issue/a-15275219> accessed on 22 June 2023; Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 'One Health: Zoonotic diseases' National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, 1 July 2021 <https://www.cdc.gov/onehealth/basics/zoonotic-diseases.html> accessed on 22 June 2023.

[viii] Tamara Kartal & Dr. Amit Chaudhari, 'Owned Dog Population and Knowledge, Attitude and Practices (KAP) Survey Report for Machakos County, Kenya' Humane Society International, 2017, 16.

[ix] World Health Organisation in partnership with World Society for the Protection of Animals, 'Guidelines for dog population management, Geneva, 1990, 11.

[x] Tamara Kartal & Dr. Amit Chaudhari, 'Owned Dog Population and Knowledge, Attitude and Practices (KAP) Survey Report for Machakos County, Kenya' Humane Society International, 2017, 1.

[xi] Tamara Kartal & Dr. Amit Chaudhari, 'Owned Dog Population and Knowledge, Attitude and Practices (KAP) Survey Report for Machakos County, Kenya' Humane Society International, 2017, 7.

[xii] The Constitution of Kenya (2010), article 43(1)(a); Fourth Schedule, part II, section 1(d).

[xiii] World Organisation for Animal Health, 'Guidelines on stray dog population control' ANNEX XVII (2009).

[xiv] Control of stray dog's bill (2019).

[xv] Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act (No. 12 of 2012), section 2; Fertilizer and Animal Foodstuffs Act (No. 20of 2015), section 2.

[xvi] Wildlife conservation and Management Act (No. 47 of 2013), section 3; Fertilizer and Animal Foodstuffs Act (No. 20of 2015), section 2.

[xvii] Wildlife conservation and Management Act (No. 47 of 2013), section 3.

[xviii] Animal Disease Rules (1968), section 2.

[xix] Section 2 of the Rabies Act (Cap 365) has defined a stray dog as any dog that is wandering at large at any public place which is peculiar as there are domestic stray dogs which have owners and there are dogs that lack owners.

[xx] Nairobi City County Dog Control and Welfare (No. 10 of 2015).

[xxi] Control of stray dogs bill (2019), section 6(1)(c).

[xxii] World Health Organisation in partnership with World Society for the Protection of Animals, 'Guidelines for dog population management, Geneva, 1990, 6.

[xxiii] Animal protection and welfare bill (2019).